mRNA therapeutics in cancer immunotherapy

ADVANTAGES:

Enables druggability of intracellular, transmembrane, and secreted proteins.

Restores gene expression without risk of genomic integration.

Druglike behavior: ability to repeat dose and adjust dose/dose interval.

Endogenous post-transcriptional modifications increase probability of correct folding, glycosylation, and trafficking of the protein and decrease risk of immunogenicity.

Minimal changes to the manufacturing process for multiple targets.

Rapid development from target gene selection to product candidate.

CHALLENGES:

Stability: mRNA is susceptible to degradation.

Delivery: LNPs must be tissue-specific and biodegradable.

Immunogenicity: risk of activating the immune system via Toll-like and retinoic acid–inducible gene–like receptors.

Manufacturing: difficult to achieve high quality and highly pure mRNA with scalable manufacturing processes/

APPLICATIONS:

Because of the central role of mRNA in protein expression, mRNA technology has broad applicability in the treatment or prevention of disease.

Two mRNA-based coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines have Emergency Use Authorization, demonstrating the clinical validation of this revolutionary approach.

mRNA replacement therapy for genetic diseases is being developed for lung and liver diseases (inhaled and intravenous delivery).

Immuno-oncologic approaches can leverage the intrinsic immune adjuvant effects of mRNA.

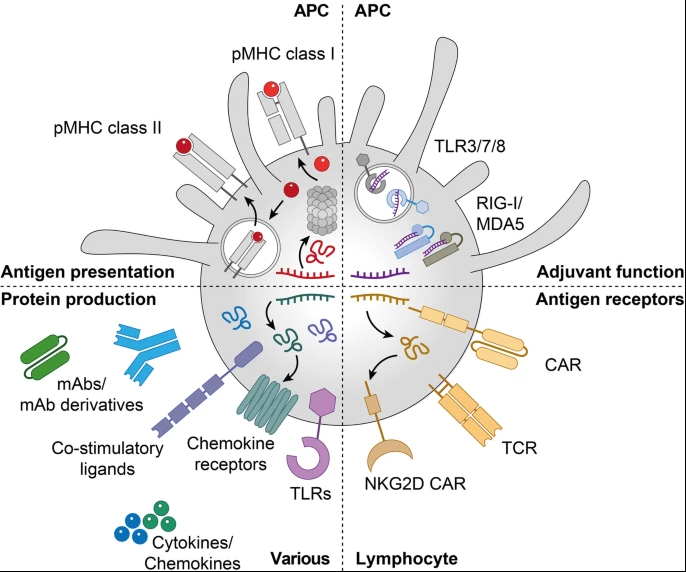

mRNA therapeutics in cancer immunotherapy. mRNA is used for anti-cancer vaccination, where it delivers cancer antigens to APCs for the presentation on MHC class I and II (top left) and stimulates innate immune activation by binding to PRRs expressed by APCs (top right), introduces antigen receptors such as CARs and TCRs into lymphocytes (bottom right), and allows the expression of immunomodulatory proteins including TLRs, chemokine receptors, co-stimulatory ligands, cytokines, chemokines and different mAb formats in various cell subsets (bottom left). APC: antigen-presenting cell; CAR: chimeric antigen receptor; mAb: monoclonal antibody; MDA5: melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5; pMHC: peptide-major histocompatibility complex; NKG2D: natural killer group 2D; PRR: pattern recognition receptors; RIG-I: retinoic acid-inducible gene 1; TCR: T-cell receptor; TLR: Toll-like receptor

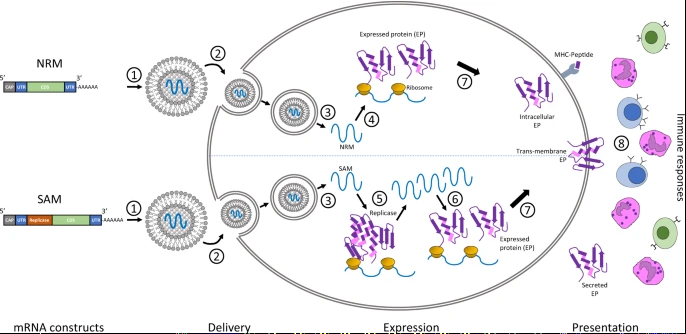

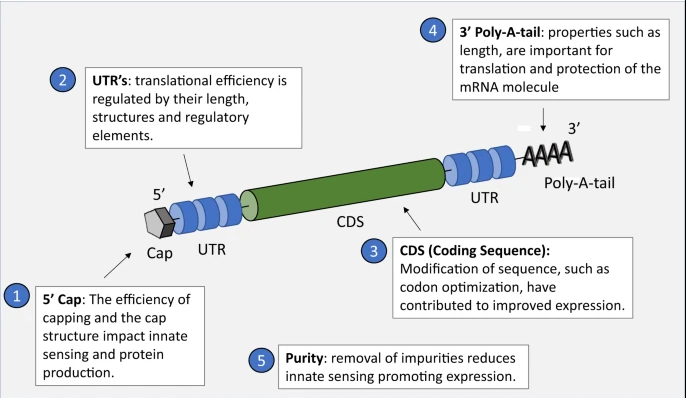

The core principle behind mRNA as a technology for vaccination is to deliver the transcript of interest, encoding one or more immunogen(s), into the host cell cytoplasm where expression generates translated protein(s) to be within the membrane, secreted or intracellularly located. Two categories of mRNA constructs are being actively evaluated: non-replicating mRNA (NRM) and self-amplifying mRNA (SAM) constructs (Fig. 1). Both have in common a cap structure, 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs), an open-reading frame (ORF), and a 3′ poly(A) tail.3 SAM differs with the inclusion of genetic replication machinery derived from positive-stranded mRNA viruses, most commonly from alphaviruses such as Sindbis and Semliki-Forest viruses.4,5 Generally, the ORF encoding viral structural proteins is replaced by the selected transcript of interest, and the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase is retained to direct cytoplasmic amplification of the replicon construct.

A rationally designed mRNA delivery system can fulfill at least four roles: promote mRNA entrapment efficiency, protect the mRNA from degradation, enable cellular uptake, and facilitate endosomal escape

In general, nanoparticles undergo endosomal escape by three hypothetical pathways: i) dissociation/destabilization under acidic lumen of endosome; ii) fusion of liposomes with endosomal membrane, and iii) rupture of endosomal membranes. Different nanoconstructs exploit different pathway(s): for example, ‘pH-responsive endosomal escape’ and ‘proton sponge effect’. 1) pH-responsive conformational changes due to protonation, or cleavage of a bond in the polymer at endosomes lead to ‘pH-responsive endosomal escape’ (18). Cationic lipids may interact with the negatively charged endosomal membrane to facilitate endosomal escape (14). DOPE becomes fusogenic following the protonation of its head group at acidic conditions, leading to the formation of a hexagonal (HII) phase and temporarily destabilizing the endosomal membrane; 2) Cationic polyplexes are considered to undergo endosomal escape through the ‘proton sponge effect’, where endocytosed polyplexes induce an osmotic swelling of the endosome due to the influx of protons and eventually cause the endosome to rupture (14).

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11095-021-03015-x